The Fire Eaters

By Gordon Leidner — Great American History

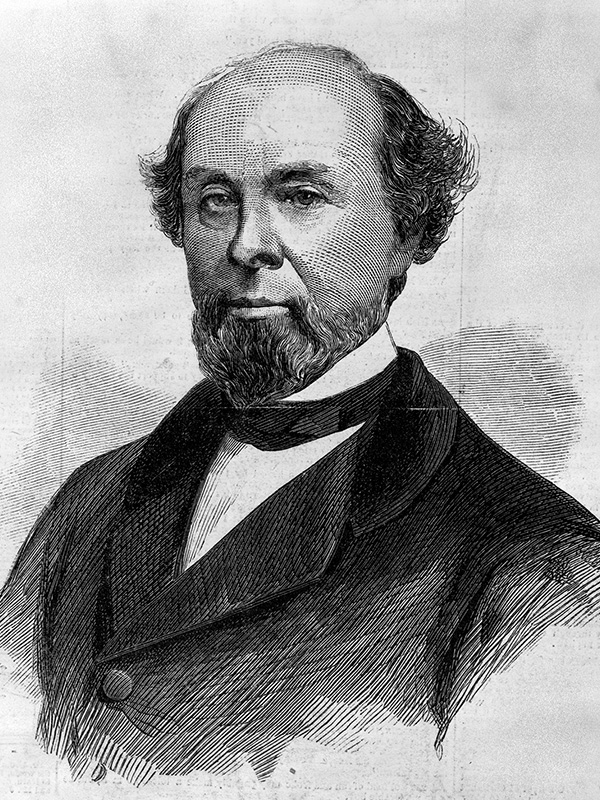

Robert Barnwell Rhett

(1800-1876)

Born to an aristocratic South Carolina family on December 21, 1800, Robert Barnwell Rhett became a lawyer, a slave owner, and, most importantly, a political leader of the South. As one of the earliest secession advocates in South Carolina, he was a supporter of Nullification during the Jackson Administration.

He spent much of his life working for an independent South. Convinced that only a Republican victory in the presidential race of 1860 would bring about an independent southern nation, he and other southern political leaders labored hard to bring this about. After Lincoln won the presidential nomination in 1860, he drafted South Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession and the next year took part in writing of the Confederate Constitution.

Rhett gained for himself the title of the “Father of Secession.” His politics were considered too extreme for the presidency, though, and the more moderate Jefferson Davis was selected in his place.

As one of the owner-editors of the Charleston Mercury, he became a harsh critic of the Davis administration. By 1863, his fire-eater secessionism had been recognized as too extreme, and he was defeated in a race for a seat in the Confederate Congress. When the Civil War ended, he refused to apply for a pardon. He died in St. James Parish, La., September 14, 1876. He is buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, S.C.

He spent much of his life working for an independent South. Convinced that only a Republican victory in the presidential race of 1860 would bring about an independent southern nation, he and other southern political leaders labored hard to bring this about. After Lincoln won the presidential nomination in 1860, he drafted South Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession and the next year took part in writing of the Confederate Constitution.

Rhett gained for himself the title of the “Father of Secession.” His politics were considered too extreme for the presidency, though, and the more moderate Jefferson Davis was selected in his place.

As one of the owner-editors of the Charleston Mercury, he became a harsh critic of the Davis administration. By 1863, his fire-eater secessionism had been recognized as too extreme, and he was defeated in a race for a seat in the Confederate Congress. When the Civil War ended, he refused to apply for a pardon. He died in St. James Parish, La., September 14, 1876. He is buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, S.C.

For further reading: A Fireater Remembers:The Confederate Memoir of Robert Barnwell Rhett edited by William C. Davis. Or, Men of Secession by James Abrahamson.

Order: Davis’s A Fireater Remembers Now

Order: Abrahamson’s Men of Secession Now

Order: Davis’s A Fireater Remembers Now

Order: Abrahamson’s Men of Secession Now

William Lowndes Yancey

(1814-1863)

Often called “The Orator of Secession,” Yancey was one of the most extreme of advocates of state rights and slavery. Yancey’s “Alabama Platform” demanded that southerners have the right to take their slaves into western territories and greater assurances of state rights.

He served in the Alabama state legislature in the early 1840s and sat in the US Congress until his first debate-which resulted in a duel with future Confederate General Thomas L. Clingman-prompted him to resign. Over the years his belief in the inalienable rights of the states grew. He opposed the Compromise of 1850, and proposed a Southern confederacy as early as 1858.

Convinced that only a Republican victory would convince the South that they must withdraw from the Union, Yancey pushed hard to split the Democratic party in 1860. He opposed the Democratic frontrunner Stephen A. Douglas’ candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. After the Democratic party split, he threw his support behind John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky. He drew up Alabama’s Secession Ordinance after Lincoln was elected president.

Following his work at the Alabama secession convention he was sent to England and France by Jefferson Davis to seek recognition for Confederacy. While abroad he was elected to the Confederate Senate, and he returned to take his seat on March 27, 1862. He served on the committees on: Foreign Affairs, Naval Affairs; Public Lands; and Territories. As a strong “states rightist,” he came into conflict with Davis’ idea of a strong central government. He constantly wanted to limit the president’s powers, especially in the field of appointments, and wanted to require the payment of market prices for impressed goods. He died at his home between congressional sessions on July 23, 1863.

He served in the Alabama state legislature in the early 1840s and sat in the US Congress until his first debate-which resulted in a duel with future Confederate General Thomas L. Clingman-prompted him to resign. Over the years his belief in the inalienable rights of the states grew. He opposed the Compromise of 1850, and proposed a Southern confederacy as early as 1858.

Convinced that only a Republican victory would convince the South that they must withdraw from the Union, Yancey pushed hard to split the Democratic party in 1860. He opposed the Democratic frontrunner Stephen A. Douglas’ candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. After the Democratic party split, he threw his support behind John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky. He drew up Alabama’s Secession Ordinance after Lincoln was elected president.

Following his work at the Alabama secession convention he was sent to England and France by Jefferson Davis to seek recognition for Confederacy. While abroad he was elected to the Confederate Senate, and he returned to take his seat on March 27, 1862. He served on the committees on: Foreign Affairs, Naval Affairs; Public Lands; and Territories. As a strong “states rightist,” he came into conflict with Davis’ idea of a strong central government. He constantly wanted to limit the president’s powers, especially in the field of appointments, and wanted to require the payment of market prices for impressed goods. He died at his home between congressional sessions on July 23, 1863.

For further reading: The Life and Times of William Lowndes Yancey by John Witherspoon DuBose. Men of Secession by James Abrahamson.

Order: Dubose’s The Life and Times of William Lowndes Yancey Now

Order: Abrahamson’s Men of Secession Now

Order: Dubose’s The Life and Times of William Lowndes Yancey Now

Order: Abrahamson’s Men of Secession Now

Louis Trezevant Wigfall

(1816-1874)

Louis T. Wigfall was born near Edgefield, South Carolina on April 21, 1816. After graduating from South Carolina College in 1837, he moved to Texas in 1848 and served in the Texas legislature. After enterring the US Senate in 1859, he became a leader in the effort to assure southern slave-owner’s freedom to settle in the territories with their slaves.

Insisting that the Democratic party platform of 1860 call for the Federal government to guarantee protection of slavery in the territories, he was key to the split of the Democratic party and the subsequent election of Abraham Lincoln as president.

He was admitted to the Provisional Confederate Congress on April 29, 1861, where he served on the Committee on Foreign Affairs. Earlier that month he had played a leading role in arranging Fort Sumter’s surrender, and soon decided to enter military service.

After several assignments of brigade command, he resigned on February 20, 1862 and took a seat in the First Regular Congress and served throughout the war. He sat on the committees on Foreign Affairs; Military Affairs; Territories; and Flag and Seal. An arrogant man who had fought two prewar duels, Wigfall came into conflict with President Davis. After the chief executive vetoed Wigfall’s bill to upgrade staff positions in the army and limit presidential selection, Wigfall carried his fight into social circles, even going so far as to refuse to stand when Davis entered the room. Although a friend and supporter of the Confederate military, he was also an obstructionist in opposing Davis’ nominations. He spent six years in self-imposed exile in England before returning via Baltimore to Texas, never adjusting to defeat.

Insisting that the Democratic party platform of 1860 call for the Federal government to guarantee protection of slavery in the territories, he was key to the split of the Democratic party and the subsequent election of Abraham Lincoln as president.

He was admitted to the Provisional Confederate Congress on April 29, 1861, where he served on the Committee on Foreign Affairs. Earlier that month he had played a leading role in arranging Fort Sumter’s surrender, and soon decided to enter military service.

After several assignments of brigade command, he resigned on February 20, 1862 and took a seat in the First Regular Congress and served throughout the war. He sat on the committees on Foreign Affairs; Military Affairs; Territories; and Flag and Seal. An arrogant man who had fought two prewar duels, Wigfall came into conflict with President Davis. After the chief executive vetoed Wigfall’s bill to upgrade staff positions in the army and limit presidential selection, Wigfall carried his fight into social circles, even going so far as to refuse to stand when Davis entered the room. Although a friend and supporter of the Confederate military, he was also an obstructionist in opposing Davis’ nominations. He spent six years in self-imposed exile in England before returning via Baltimore to Texas, never adjusting to defeat.

For further reading: Louis Wigfall: Southern Fire-Eater by A. L. King. Men of Secession by James Abrahamson.

Order: King’s Louis T. Wigfall: Southern Fire Eater Now

Order: Abrahamson’s Men of Secession Now

Order: King’s Louis T. Wigfall: Southern Fire Eater Now

Order: Abrahamson’s Men of Secession Now