The Thirteenth Amendment

By Gordon Leidner — Great American History

The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, abolished slavery as a legal institution.

The Constitution, although never mentioning slavery by name, refers to slaves as “such persons” in Article I, Section 9 and “a person held to service or labor” in Article IV, Section 2. The Thirteenth Amendment, in direct terminology, put an end to this. The amendment states:

The Constitution, although never mentioning slavery by name, refers to slaves as “such persons” in Article I, Section 9 and “a person held to service or labor” in Article IV, Section 2. The Thirteenth Amendment, in direct terminology, put an end to this. The amendment states:

Section 1: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2: Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Background

The history behind this amendments adoption is an interesting one. Prior to the Civil War, in February 1861, Congress had passed a Thirteenth Amendment for an entirely different purpose–to guarantee the legality and perpetuity of slavery in the slave states, rather than to end it. This amendment guaranteeing slavery was a result of the complicated sectional politics of the antebellum period, and a futile effort to preclude Civil War. Although the Thirteenth Amendment that guaranteed slavery was narrowly passed by both houses, the Civil War started before it could be sent to the states for ratification.

But the final version of the Thirteenth Amendment–the one ending slavery–has an interesting story of its own. Passed during the Civil War years, when southern congressional representatives were not present for debate, one would think today that it must have easily passed both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Not true. As a matter of fact, although passed in April 1864 by the Senate, with a vote of 38 to 6, the required two-thirds majority was defeated in the House of Representatives by a vote of 93 to 65. Abolishing slavery was almost exclusively a Republican party effort–only four Democrats voted for it.

It was then that President Abraham Lincoln took an active role in pushing it through congress. He insisted that the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment be added to the Republican party platform for the upcoming presidential elections. He used all of his political skill and influence to convince additional democrats to support the amendments’ passage. His efforts finally met with success, when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119-56. Finally, Lincoln supported those congressmen that insisted southern state legislatures must adopt the Thirteenth Amendment before their states would be allowed to return with full rights to Congress.

The fact that Lincoln had difficulty in gaining passage of the amendment towards the closing months of the war and after his Emancipation Proclamation had been in effect 12 full months, is illustrative. There was still a reasonably large body of the northern people, or at least their elected representatives, that were either indifferent towards, or directly opposed to, freeing the slaves.

But the final version of the Thirteenth Amendment–the one ending slavery–has an interesting story of its own. Passed during the Civil War years, when southern congressional representatives were not present for debate, one would think today that it must have easily passed both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Not true. As a matter of fact, although passed in April 1864 by the Senate, with a vote of 38 to 6, the required two-thirds majority was defeated in the House of Representatives by a vote of 93 to 65. Abolishing slavery was almost exclusively a Republican party effort–only four Democrats voted for it.

It was then that President Abraham Lincoln took an active role in pushing it through congress. He insisted that the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment be added to the Republican party platform for the upcoming presidential elections. He used all of his political skill and influence to convince additional democrats to support the amendments’ passage. His efforts finally met with success, when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119-56. Finally, Lincoln supported those congressmen that insisted southern state legislatures must adopt the Thirteenth Amendment before their states would be allowed to return with full rights to Congress.

The fact that Lincoln had difficulty in gaining passage of the amendment towards the closing months of the war and after his Emancipation Proclamation had been in effect 12 full months, is illustrative. There was still a reasonably large body of the northern people, or at least their elected representatives, that were either indifferent towards, or directly opposed to, freeing the slaves.

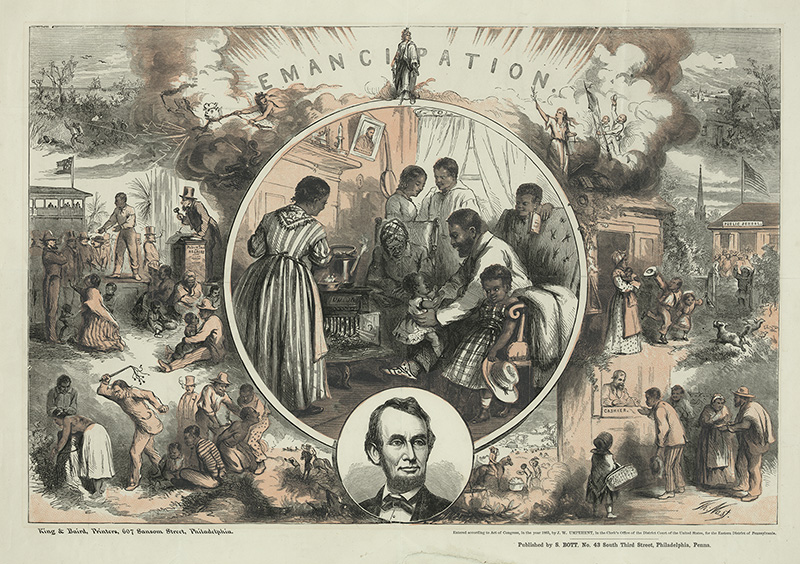

The Effect of the Emancipation Proclamation

Modern historians occasionally criticize Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, declaring it a hollow document that “freed no slaves.” Signed by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, it proclaimed that “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Lincoln correctly realized that as President, he had no legal grounds to single-handedly terminate the institution of slavery–but that this had to be done by a constitutional amendment. The Emancipation Proclamation was simply a war powers action by he, the commander in chief of the armies, in which he attempted to remove all the slaves from the southern peoples “in rebellion against the United States.” Even in this, Lincoln was very anxious about the legality of his actions. He worded the document very carefully, in legal terms, in his attempt to make it legally binding in future courts of law.

He recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed quickly by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation had no theoretical effect on the legal status of slaves in the border states, or slaves in regions of the country not currently under the control of southern armies, it had, in fact, a great deal of practical impact on the legality of slavery everywhere–North and South. As northern armies marched through the south, which General Sherman and his army soon began doing, thousands of slaves followed in their wake–and were never again under the legal authority of their former masters. So the argument that the Emancipation “freed no slaves” is a specious one. Until the Thirteenth Amendment was was fully ratified by the necessary majority of the states in December of 1865, the Emancipation Proclamation was the document used to justify separating slaves from their masters, and by late 1865 there were no slaves remaining in the United States. Consequently, the Emancipation Proclamation was truly the beginning of the end of slavery.

Lincoln correctly realized that as President, he had no legal grounds to single-handedly terminate the institution of slavery–but that this had to be done by a constitutional amendment. The Emancipation Proclamation was simply a war powers action by he, the commander in chief of the armies, in which he attempted to remove all the slaves from the southern peoples “in rebellion against the United States.” Even in this, Lincoln was very anxious about the legality of his actions. He worded the document very carefully, in legal terms, in his attempt to make it legally binding in future courts of law.

He recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed quickly by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation had no theoretical effect on the legal status of slaves in the border states, or slaves in regions of the country not currently under the control of southern armies, it had, in fact, a great deal of practical impact on the legality of slavery everywhere–North and South. As northern armies marched through the south, which General Sherman and his army soon began doing, thousands of slaves followed in their wake–and were never again under the legal authority of their former masters. So the argument that the Emancipation “freed no slaves” is a specious one. Until the Thirteenth Amendment was was fully ratified by the necessary majority of the states in December of 1865, the Emancipation Proclamation was the document used to justify separating slaves from their masters, and by late 1865 there were no slaves remaining in the United States. Consequently, the Emancipation Proclamation was truly the beginning of the end of slavery.

For further reading Lincoln and Freedom: Slavery, Emancipation, and the Thirteenth Amendment by Herman Belz, et. al.

Order: Belz’s Lincoln and Freedom Now

Order: Belz’s Lincoln and Freedom Now

Research paper topic for the Civil War: Abraham Lincoln and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment

Category: Civil War Term Papers

Abraham Lincoln and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States, is a dramatic chapter of American history. The US Constitution, when it went into effect in 1789, had guaranteed the institution of slavery in America. In the early to mid-1800’s, slavery became an increasingly divisive force in the country, with virtually the entire southern populace and many northern Democrats supporting it; and much of the North, particularly the Republican Party, opposing it. When Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the South decided to secede from the Union rather than risk the potential loss of slavery.13 Amendment

The only way slavery could be permanently ended was via passage of an amendment to the Constitution. But when Lincoln took office in 1861, the passage of an amendment to end slavery was an extremely remote possibility. Even with the departure of the South’s elected representatives from the US Congress, and the election of a Republican president that opposed slavery, the anti-slavery forces in Congress still had an uphill fight. Not only did a large percentage of northern Democrats support the continuation of slavery, but the majority of northern soldiers did not want to risk their lives for freedom for the slaves. Many had enlisted to fight for the Union, and no more.

Although he hated slavery, Lincoln recognized how most of the northern people felt about slavery when he took office, and made the primary purpose of the war effort to put down the rebellion and preserve the union of the states. But he watched for an opportunity to end slavery as well.

Ending slavery would require all of Lincoln’s leadership skills. First of all, he had to convince thousands of northern soldiers to be willing to fight, suffer, and possibly die to end slavery. He had to convince the northern public that freedom for the slaves was worth the potential sacrifice of the lives of their sons, fathers, and husbands. He had to convince the northern congressional democrats to go against their own reluctance to end slavery. He had to do all of this in the course of the most costly, bitterly-fought war the nation would ever endure.

After the Battle of Antietam, nearly eighteen months after the war began, Lincoln saw his opportunity. He decided to make use of his war powers as president to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which promised freedom to slaves in the southern states. How he gained support for this is an interesting story in itself. He had to not only to secure the support of the soldiers, but also overcome the doubt of many of the influential members of his own political party.

Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was a huge step towards freedom for the slaves, but the amendment was still necessary to guarantee it. Surprisingly, the first effort to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, ending slavery, suffered a defeat in the House of Representatives by a vote of 93 to 65. Only four democrats voted in favor of eliminating slavery.

After this defeat, Lincoln took personal charge of the effort to reverse the vote of the reluctant democrats, and managed to sway enough votes that the Thirteenth Amendment succeeded in Congress the second time. It was passed in January, 1865 by a vote of 119-56 and sent to the states for ratification.

Questions that could be researched on the subject of Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment are: (1) Why did northern democrats oppose the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, and who were the democrats that switched their vote? (2) How did Lincoln convince them to change sides? (3) What would have happened if Lincoln had not quickly intervened, or had been assassinated before the Thirteenth Amendment passed–would slavery have been left intact at the war’s close? (4) Finally, and this is probably the most complicated, how did Lincoln convince the northern soldiers and northern people to lay aside their personal interests and make the sacrifices necessary to free the slaves?

Great American history has numerous resources on these subjects, including The Thirteenth Amendment, Lincoln the Transformational Leader, and the Outline of the Civil War.

Abraham Lincoln and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States, is a dramatic chapter of American history. The US Constitution, when it went into effect in 1789, had guaranteed the institution of slavery in America. In the early to mid-1800’s, slavery became an increasingly divisive force in the country, with virtually the entire southern populace and many northern Democrats supporting it; and much of the North, particularly the Republican Party, opposing it. When Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the South decided to secede from the Union rather than risk the potential loss of slavery.13 Amendment

The only way slavery could be permanently ended was via passage of an amendment to the Constitution. But when Lincoln took office in 1861, the passage of an amendment to end slavery was an extremely remote possibility. Even with the departure of the South’s elected representatives from the US Congress, and the election of a Republican president that opposed slavery, the anti-slavery forces in Congress still had an uphill fight. Not only did a large percentage of northern Democrats support the continuation of slavery, but the majority of northern soldiers did not want to risk their lives for freedom for the slaves. Many had enlisted to fight for the Union, and no more.

Although he hated slavery, Lincoln recognized how most of the northern people felt about slavery when he took office, and made the primary purpose of the war effort to put down the rebellion and preserve the union of the states. But he watched for an opportunity to end slavery as well.

Ending slavery would require all of Lincoln’s leadership skills. First of all, he had to convince thousands of northern soldiers to be willing to fight, suffer, and possibly die to end slavery. He had to convince the northern public that freedom for the slaves was worth the potential sacrifice of the lives of their sons, fathers, and husbands. He had to convince the northern congressional democrats to go against their own reluctance to end slavery. He had to do all of this in the course of the most costly, bitterly-fought war the nation would ever endure.

After the Battle of Antietam, nearly eighteen months after the war began, Lincoln saw his opportunity. He decided to make use of his war powers as president to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which promised freedom to slaves in the southern states. How he gained support for this is an interesting story in itself. He had to not only to secure the support of the soldiers, but also overcome the doubt of many of the influential members of his own political party.

Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was a huge step towards freedom for the slaves, but the amendment was still necessary to guarantee it. Surprisingly, the first effort to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, ending slavery, suffered a defeat in the House of Representatives by a vote of 93 to 65. Only four democrats voted in favor of eliminating slavery.

After this defeat, Lincoln took personal charge of the effort to reverse the vote of the reluctant democrats, and managed to sway enough votes that the Thirteenth Amendment succeeded in Congress the second time. It was passed in January, 1865 by a vote of 119-56 and sent to the states for ratification.

Questions that could be researched on the subject of Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment are: (1) Why did northern democrats oppose the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, and who were the democrats that switched their vote? (2) How did Lincoln convince them to change sides? (3) What would have happened if Lincoln had not quickly intervened, or had been assassinated before the Thirteenth Amendment passed–would slavery have been left intact at the war’s close? (4) Finally, and this is probably the most complicated, how did Lincoln convince the northern soldiers and northern people to lay aside their personal interests and make the sacrifices necessary to free the slaves?

Great American history has numerous resources on these subjects, including The Thirteenth Amendment, Lincoln the Transformational Leader, and the Outline of the Civil War.